The Black Church is embracing LGBTQ+ youth and reuniting faith with family. Will it help reduce homelessness?

This is the second story in a series about the Black Church in Los Angeles, and its social, economic, political and cultural impacts. Read the first installment.

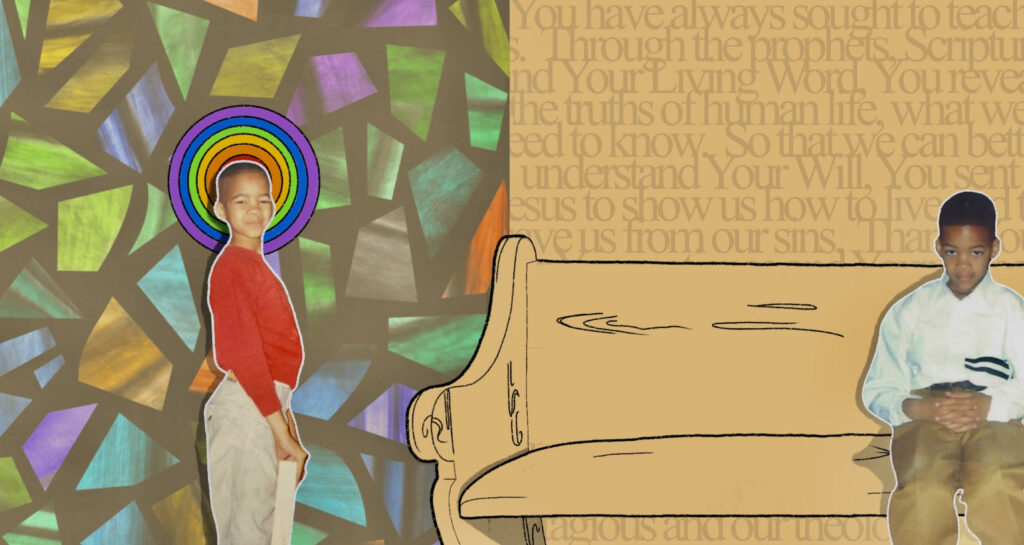

Church is where I first heard talk about gay people. Homosexuality was a frequent topic, often discussed with disdain or pity. Within those sacred walls, we were a constant punching bag. Sitting in the pews or behind the pulpit in my choir robe, I cringed when the pastor called me an abomination. I tried (unsuccessfully) to hide my attraction to boys.

Week after week, I heard I was going through a phase. That my homosexuality was a trial or tribulation I needed to overcome. That I should repent. Stop practicing that lifestyle. Hundreds of people in the congregation nodded their heads or cried out ‘Preach!’ at any mention about gay sin. They yelled ‘Amen!’ when they heard gays would go to hell unless we turned from our wicked ways. My parents were unknowingly among them. Those messages coming from the pulpit were the beginning of an unspoken chasm in our relationship. I did not feel safe. Over time, the distance between us grew wider.

In 2021, the Homeless Outreach Program Integrated Care System (HOPICS) in Los Angeles launched a program designed to build bridges that reunite LGBTQ+ transitional-age youth 18-24 with their families. The initiative between faith-based groups, parents and LGBTQ+ youth hopes to make a dent in the nearly 4.2 million unhoused youth across the U.S., according to researchers at Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. Their study found that LGBTQ+ young adults experience homelessness at more than twice the rate of their straight peers.

Luis Quinones, parent and faith community coordinator at HOPICS, said this is why churches are waking up. “We can’t argue the realities and first hand stories [of LGBTQ+ youth who are unhoused].”

Quinones told me eight churches in South Los Angeles joined the pilot for a one-year commitment. Those pastors agreed to listening sessions with youth and parents. They are also providing on-site housing resources at their churches, along with outreach events.

As LGBTQ+ youth step into legal adulthood, many find themselves navigating the stark reality of independence without the financial or emotional readiness to face the world alone. If they are unhoused, they are entering a world where they face, or are already facing, criminalization. The U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments in April to determine if local governments can make it a crime to involuntarily live outside when adequate shelter is not available.

For those who are believers, the road toward self acceptance comes littered with traumas inflicted by people–and governments–who should embrace them unconditionally.

The ties that break

Coming out at 16 years old was an act of self-determination that led to slowly distancing myself from church. I rebelled by sneaking out to meet up with guys. Fast forward two years, tensions between my parents and me were palpable. They insisted I follow their rules and the teachings of the Bible or I had to go.

So, I left.

I went to my bedroom, quickly stuffed my meager belongings into trash bags and tossed them in the trunk of my white two-door Chevrolet Cavalier. Heart racing, I pulled away from the modest split-level brick house where I had lived since fifth grade. I had no savings. I did not have an apartment. I drove six miles away to the townhouse of a high school friend. I slept on a couch in the unfinished basement.

It was the first time I experienced homelessness. It would not be the last.

Decades have passed since that consequential day in the D.C.-area suburban neighborhood I called home. I’ve since moved to Los Angeles, but not much has changed. Last year, more than 3,700 transition-age youth experienced homelessness across Los Angeles on any given night, a 33% increase from 2022. (In part, L.A. housing officials said the spike can be attributed to a new methodology authorized by the Housing and Urban Development Department. Surveys were conducted in person and also allowed by phone.) According to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, they are disproportionately Black, Latine and more likely to report being LGBTQ+. Safe places for transgender or nonbinary people experiencing homelessness to go are scarce. And much like Tryron Ramsey, a Black youth I met in 2021, they are often unemployed and without a support network. His grandfather, a Jehovah’s Witness, kicked him out for being gay two weeks before Thanksgiving. Ramsey spent several nights outdoors before finding his way to the Los Angeles LGBT Center where he slept in one of 40 emergency shelter beds.

“I want to stop young people from being in these violent situations and dying because of all the stuff they are exposed to on the streets. I don’t know if this will work, but we want to try.”

– Veronica Lewis, HOPICS director

“So much of what [LGBTQ+ youth] experience is people from their church communities that aren’t there for them,” said Erin Casey, director of programs for My Friend’s Place, a drop-in center in Hollywood that provides services to youth experiencing homelessness. Casey noted that during fiscal year 2023, her colleagues helped 835 people; 45% of those walk-ins identified as LGBTQ+ and 88% were Black, Indigenous and people of color.

“They say, ‘I came out, I was rejected, and now I’m on the streets.’ We hear that all the time,” Casey told me.Transitional-age youth need more “hands on” support since they are new adults going through a crisis and often lack extensive work history or college experience, according to Sage Johnson, an advisory board member at the UC San Francisco Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative. At a February webinar, discussing a new report aimed at understanding the experiences of Black unhoused Californians, Johnson said it wasn’t always religious reasons for which LGBTQ+ Black youth were kicked out of their house.

“Their parents, or whoever they were staying with, was unable to accept who they were so they were asked to leave,” Johnson said during a Q&A at the webinar. “That’s when the necessity of community comes in. When the household fails, it becomes a necessity for someone else in the community to uphold that young person.”

HOPICS Director Veronica Lewis, whose husband is a non-denominational Christian minister, questioned how parents can allow their children to be who they are without conflicting with their beliefs, which results in kids being kicked out of their family homes.

“I want to stop young people from being in these violent situations and dying because of all the stuff they are exposed to on the streets,” Lewis said. “I don’t know if this will work, but we want to try.”

Finding a way home

Amid stories of isolation and estrangement from family that lead to continued instability, one goal of the HOPICS bridge program is to reunite 25 youth with their families by June. But some youth don’t want to return to their families; Quinones said they want to prove they can make it on their own.

Proving I could make it on my own came with challenges. In 2000, at age 18, I dropped out of university, trading textbooks for the pulsating lights of gay clubs and the ballroom scene. I had several minimum-wage jobs that included stints as a make-up artist, retail worker and selling long-distance phone services. I grieved the loss of friends who died from drug overdoses or AIDS-related illnesses. I faced financial hardships. There were times I stole out of desperation to pay rent, resulting in legal troubles. I spiraled into severe depression. During these years, I experienced romantic love and heartbreak. I had minimal contact with my parents. Sixteen years would pass before I returned to college.

Church was a distant memory. I wondered if anything would be different if I were “saved,” that is accepting Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior. The Bible says when this happens, people are born again, forgiven and delivered from the penalties of sin. Christians are taught they must do this in order to have eternal life and go to heaven. But that is complicated for LGBTQ+ people.

“In their mind, [Christians] are operating from a place of love. But I do think that the church and homophobic Christians rely on Biblical misinterpretation that needs to be unlearned and unpacked in a safe and healthy way where everyone can feel heard.”

– Dontá Morrison, minister at Church One Ministries, Long Beach

Dontá Morrison wrote in his 2021 dissertation that in the Black Church, a place central to Black community life, Black Christian men who have sex with men often face painful contradictions: Their racial and sexual identities clash with traditional religious beliefs that vilify homosexuality, leading to exclusion and marginalization. His research found that while the church is a source of support and unity for many, it can also be a space for public shaming and alienation, forcing many people to choose between their faith and being their true selves.

When we talked, Morrison expressed concern that many churches lead with, ‘You would not be homeless if you were straight. Come to my church so you can get straight. Then God will bless you.’ But he insisted God’s blessings are not determined by sexual identity.

“I don’t want to go to a gay heaven,” Morrison told me. “I can’t imagine spending eternity with a bunch of gay people. I need some diversity up in the space.”

In a December New York Times essay, author and Baptist preacher Michael Eric Dyson examined how Beyoncé’s 2023 Renaissance World Tour brought all types of people together, an example of what church at its best should be. Dyson wrote that he admired the Black Church’s “noble commitment to moral ardor and social justice.” However, he noted that the Church falls short in extending love and compassion for “queer folk.”

The Black Church is complex. During the civil rights era, some congregations and pastors shied away from civil disobedience and nonviolent protests. Today, there are similar splits in attitudes towards movements like Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ+ rights. But Morrison believes Black churchgoers can change. He recalled a two-year dialogue with Bishop W. Todd Ervin, Sr. of Church One Ministries in Long Beach, focused on homosexuality and the Bible. A pivotal turning point came in 2016 after the massacre of 49 people at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida.

“[My bishop] saw how [the massacre] broke my spirit,” Morrison said. “That’s when he said enough is enough. The following Sunday, he allowed me to openly tell the church I’m gay, and he backed me.”

The bishop also encouraged people in the congregation to stand if they wished to acknowledge their sexual identity, said Morrison. “It was transformative and the church hasn’t been the same since.”

A blueprint for building bridges

The Black Church stands at a crossroads between tradition and transformation. But some churches’ involvement in the HOPICS program marks a step in the right direction. If the pilot is successful, it could be a blueprint for churches in other cities grappling with homelessness. Quinones told me there are plans to create an online toolkit for pastors to start conversations about the intersection of queer identity and church, without requiring theological changes.

“My hope was that the bridge program would be a way for me to be engaged with the [LGBTQ+] community in South L.A.,” said Gary Williams, pastor of Saint Mark United Methodist Church, which joined the program in 2022.

Williams said changing his views on homosexuality was a journey that spanned decades. It started with growing up believing he was his father’s only child, only to discover his father had another son. Williams eventually formed a bond with his “smart, sharp and brilliant” older gay brother. Although some family members accepted his brother, their father did not. When his brother died in 1983, Williams said neither he nor his parents attended the funeral.

“I held on to that for a long time.”

Williams now has a 44-year-old son. The 67-year-old father admitted they did not always have the best relationship. But after suspecting his son might be gay, he reached out to begin the process of mending fences. In a first for him as a pastor, Williams officiated his son’s wedding in 2014.

The journey to accepting LGBTQ+ people is something Williams hopes the Black Church is able to do eventually. “I believe they want to do the right thing, but they can’t bring themselves to step outside of the old church model that has run folk away,” he said.

Williams acknowledged that some people may feel uneasy by him welcoming LGBTQ+ people, but so far, he’s heard no pushback from the congregation. He hopes the church is headed in a direction where the next pastor could be gay or gay friendly.

“To come into a traditional Black church, I couldn’t change it overnight,” Williams told me. “But the ground is being tilled, and I’ve been planting little seeds throughout the whole eight years [I’ve been pastor]. I preach a lot of love and that we are all made in the image of God.”

For Adrienne Zackery, lead pastor of Crossroads United Methodist Church in Compton, joining the HOPICS Bridge Program in 2022 was an opportunity to heal the community through outreach.

“I grew up in the church, but it was always a hypocritical relationship between [LGBTQ+] people and faith leaders,” Zackery explained. “One thing I’ve learned is the harm that has caused the queer community. Once we identified this group and the need, that crystalized for me what it meant to be an ally in this work.”

During a summit at Crossroads in December 2023, Zackery said she brought faith leaders and queer people together to discuss their positions in a safe space. At a similar summit in Houston in January, she joined faith leaders and queer people from around the country for a conversation on inclusion.

“The common denominator of scripture is that all humanity is made in the image and likeness of God and that is the premise in how we move forward in this journey to love,” Zackery said. “It has been a transformation. I can’t tell you how many doors God has opened for us to have this courageous conversation.”

Zackery told me Crossroads hasn’t reunited queer youth with their estranged parents. At least, not yet. But she sees the church’s work connecting youth with housing, doctors, education and access to mental health as laying a strong foundation. The church has a dedicated staff member available to support anyone who walks through its doors. She said their commitment to the bridge program is long term.

“The endgame for me is that there is a healing of the individual and the queer person will see they are unconditionally loved and accepted,” Zackery told me. “That will mend relationships between children and families.”

That’s a message my younger self would have loved to hear from the pulpit.